An insight into the London of Harry’s early career and later life. A look at the technological advances that were taking place and the underlying influencers of the time…

This Page

Harry by Gaslight

Transport, Communications, Coal, & Electricity

West End Opulence & Horse Manure

Smog & Squalor

Street Lights & Shopping

The East End

The Other Family

The Ripper

Sanitation

Attacks on Victorian Christian Morality

Marxists, Fabians, & Social Campaigners

Prostitution and Drugs

Sexual Morality

Harry by Gaslight

Harry’s London, when he started on his career in the early 1880s, was the early Victorian London of gaslight, horse drawn vehicles, and music hall entertainment. Through the rest of his lifetime he was to see the gaslight superseded by electric, the horse largely superseded by motor and rail transport, the music hall lose popularity to the cinema, and marked reductions in both the levels of poverty and crime.

A fascinating glimpse of early forms of transport in Harry’s London at the turn of the century

Writing in the year 1936 he describes London when he first lived there in 1877 when he was aged eighteen, until 1884 when he moved to Bournemouth at the age of twenty-five:

Shaftesbury Avenue, a shopping and theatre street now, was a road of small houses – a road with a naughty reputation, too. Piccadilly Circus scarcely existed. The Pavilion Theatre was a sing-song place. Old Nicol-who died a millionaire-reigned at the Café Royal.

– Leaves From My Unwritten Diary (1936)

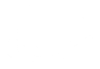

Where the Tracadero now stands was the Argyll Rooms – a gay haunt where the lads and lasses of the town roistered, danced and flirted until dawn. Night clubs as we know them were not thought of. Jazz was half a century away. The first cocktail-shaker was almost as remote. Women’s skirts trailed the pavements of Piccadilly. Abingdon Baird, who squandered two million in eleven years, was still spending.

There was plenty of gambling and cock-fighting, drinking and fighting. The bloods and bucks rolled away from favourite night haunts in hansom cabs. The horse omnibus clattered away through the night with late roisterers from Cremorne Gardens.” Romano’s “was the favourite rendezvous (for Harry’s set) when the Gaiety and Daley’s drew all the bucks and bloods, grandees and lordlings, and the musical comedy chorus supplied wives for half the susceptible peerage.”

Theatre performances were basic and satisfying, with noble heroes, and black villains (not black skinned, but referring to character) who got pelted with vegetables, usually tomatoes and cauliflowers. Ladies did not go to the stalls which were a ‘stag’ preserve; their escorts took them to the dress circle. The pit had benches without backs. Singing along to the choruses was the accepted thing.

Bob Courtney – he wore stays and painted his face, but was a husky man for all that – was chairman of the South London Music-hall by the Elephant and Castle. One paid a modest sum to go in, and the drinks one had at the tables were calculated to make the choruses go with a swing. Bessie Bellwood I remember very well at the South London. She had a welter-weight physique and stood no nonsense. I saw her roll up her sleeves in a bar once and hit out fine and dandy. She was a woman of extraordinary character, and made fast friends in all walks of life. The then Duke of Manchester would have fought a duel with anyone who made light of her name.”

– Memories (1928)

But what else was going on in London? Things were nowhere near as convivial for most of its inhabitants as they were for Harry and his mates. Britain in 1877 was at the tail end of the Industrial Revolution, and still suffering from the previous mass migration of people from a countryside where peasant farmers could no longer make a living to cities where they provided the necessary pool of cheap labour, but where they often had to live and work in appalling conditions. The population of London grew from 875,000 in 1800 to 2 million in 1850 and to 5 million by 1900, partly due to the influx from the countryside, but also due to general immigration: from Ireland following the famine of 1846, and from areas on the continent where conditions were often even worse; these immigrants being mostly Jews and Poles. By around 1870 the completion of the work of laying new railway track now saw many of the resulting out-of-work navvies arriving in London. As well as all these categories there were, of course, the many people for whom the big city has always been a magnet because of the possibility to make a ‘fast buck’ or to net a good job.

Transport, Communications, Coal, and Electricity

The fast growth of the city was made possible by the new railways, which gave previously unheard of mobility to people and goods. The first section of the underground railway was opened in 1863, running 4 miles through London from Paddington to Farringdon. It wasn’t the underground as we know it, being only covered over where necessary in order to allow the use of steam locomotives. The first electric underground railway, the ’tube’, was opened in 1890 and the basis of the present system was in place by 1907.

The growth of the telegraph system introduced fast long-distance communications without which the massive growth in trade during the era, both import and export, would not have been possible. The modernisation of farming provided the large amounts of food required daily by such a concentrated and increasing population. Unfortunately this modernisation, although inevitable and necessary, had meant the closing down of much common land and the dispossession of small peasant farmers in order to enclose the land in bigger and more efficient units, and many of the descendants of these rural refugees now crowded the slums of London.

West End Opulence & Horse Manure

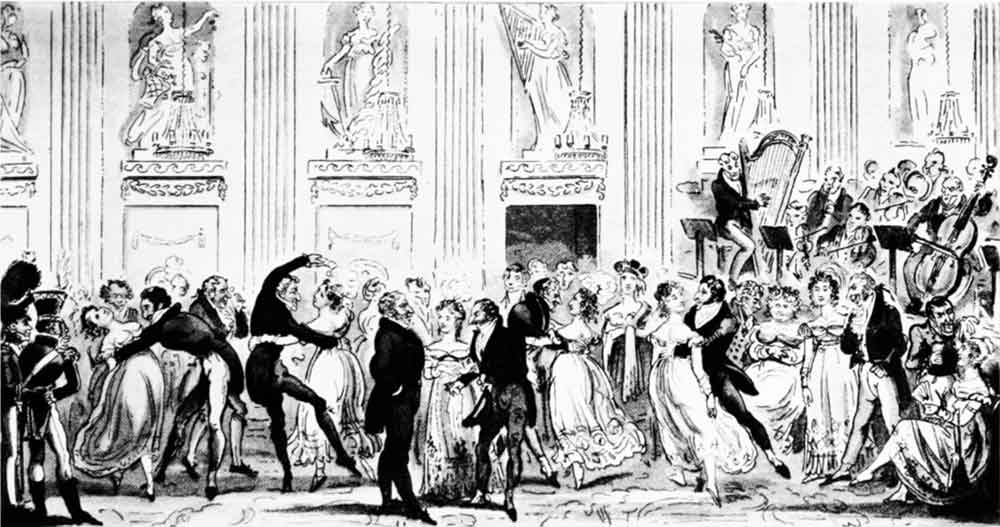

Harry’s London, after he moved to Bournemouth, was the West End, where opulent housing for the upper-classes was often arranged around exclusive and fenced-off parks forming green squares or circles, and where the Royal Palaces and Parks, government buildings, fashionable shops, hotels, theatres, restaurants, and clubs, filled most of the available space. The growing middle-classes were being accommodated in the ever expanding suburban areas now ringing the city, and escaped from their work places at night by the relatively newly built railway network and the gradually expanding Underground Railway. Transport within the city remained horse-drawn until the early part of the twentieth century, and the advent of the railway and underground only increased the requirement for horse-drawn vehicles, to take people to and from the various new stations for their journey into and out of town. London, if anything was even more chaotic and traffic clogged than it is now, on top of which the stench from the ever present horse-manure and sweating horses, especially in hot weather, was overpowering. Horse troughs lined the streets and men, or boys, were available for a penny or two to clear a way through the mire from one side of the street to the other, to prevent the upper-class ladies and gents soiling their expensive shoes and clothing.

Smog & Squalor

The exclusive use of coal burning grates pushed huge amounts of soot laden smoke into the atmosphere during the winter, turning fogs into impenetrable choking yellow murk, and causing even more chaos in the traffic laden streets. Behind the large houses in the West End were the mews – alleyways with stables and accommodation for servants. Where these mews fell into disuse they were taken over by squatters and turned into ‘rookeries’; small areas of squalor in the midst of affluence where anybody, from thieves and prostitutes, to chimney-sweeps and shoe-blacks, would doss down in order to be nearer their work. Many of the lower classes that provided the various services to the city walked miles daily to their work places.

Street Lights & Shopping

In the last few years of the century, the whole of the West End became brightly lit as electric lighting replaced the previous gas illumination. The first street lighting was installed in 1897 and very quickly after that, by 1900, the main thoroughfares and most private homes, offices, and shops became lit by electricity. Large hotels, department stores, and the various chain stores sprang up on the main thoroughfares, and the middle-classes were coaxed back into the brightly lit streets at evenings and weekends to discover the new entertainment of shopping. The consumer society was being born.

The East End

Although Harry had considerable knowledge of the seedier parts of London, having run pubs there in his early twenties, most of his upper-class friends from his new life as a hotelier would have done their best to ignore the East End, where there was a totally different world. Indeed, it was possible for the affluent to go through life without having their consciences much bothered by the conditions in which the poor lived, the West End being a virtual island from which that evidence was largely excluded. The teeming East End, where the army of people employed to service the world of their ‘betters’ largely came from, consisted of dark narrow streets of squalid tenements, where money-grabbing landlords were busy maximising their profits by forcing whole families into one or two rooms, 4 or more to a bed, with a shared toilet for several families. The East End included the port area, with its busy docks, warehouses, and factories which often relied on immigrant sweated labour (nothing much has changed). The Empire of Queen Victoria made England rich; the produce of trade fuelled by the Industrial Revolution came and went via the London docks, but left the majority of the people that serviced it poor, ill-nourished, and living in squalor. This area of London was to show some improvement in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, partly due to a slowly awakening social conscience, but mainly because of a general increase in affluence. But Harry’s London was not far removed from the London of Dickens’ Oliver Twist which was published by instalments in a literary magazine during 1837; it was still the world of the Poor Law and the ‘wurkus’.

The Other Family

Over in Whitechapel in the heart of this seething East End were living Philip Heuser and Elizabeth Muller, growing up in the households of their German immigrant fathers. Philip was born in Stepney in 1868, and Elizabeth next door in Whitechapel in the same year. In 1899 they married and in 1900 had a daughter, my mother Christina Heuser, who was to marry Jack Woodlands, Harry’s son. Neither Philip nor Elizabeth would have known anything of Harry’s West End world except, later, as part of the army of people who ventured forth from their meagre abodes to provide the services that the upper classes relied on. Philip was a coachman in 1899, so it is remotely possible that he conveyed Harry between hotels, clubs, and entertainments, or even to visit Lily. When Jack Woodlands married Christina in 1923 both Jack’s mother, Lily, and Chris’s father, Philip, were dead, so it is highly doubtful if Harry and Philip ever met socially. (Come to that, I don’t know whether Harry ever met Chris, perhaps putting in a brief appearance when she married Jack, or whether he ever saw his grandchild – me.)

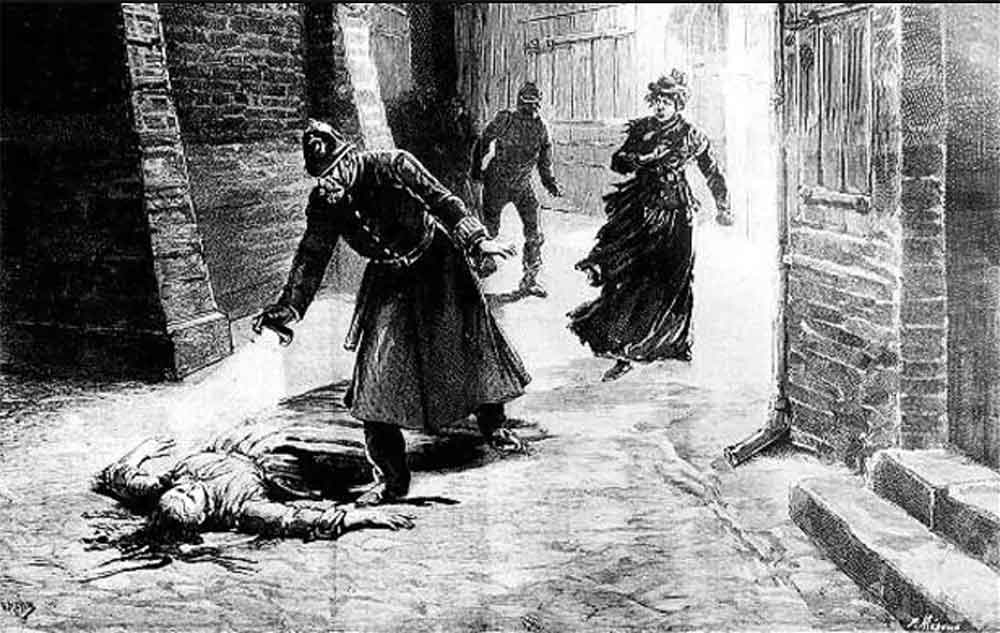

The Ripper

In 1888, when Elizabeth Muller was 19 years old, she may have been petrified at the very thought of going outside her door at night because of the Jack the Ripper murders. The second of his victims was found slashed and mutilated in Buck’s Row, Whitechapel, and while Elizabeth lived a little way outside of the East End at West Ham in 1881, her address before she was married in 1899 was back in Whitechapel, so she could have been close by the murder scene. While Harry was holding hands with one of the candidates for the Ripper title, Walter Sickert, and no doubt discussing the murders with interest or horror as was all of London, Elizabeth could have been experiencing the trauma in a more direct way.

Sanitation

Good sanitation was the answer to many diseases including cholera, but it took a long time for the message to get through. In 1858, the sewage that was randomly discharged into the Thames without anybody worrying too much about it, except the poor who inhabited the waterside slums, suddenly came to the attention of the refined and delicate nostrils of the ruling elite. Hot weather caused the ‘Great Stink’ which badly affected the Houses of Parliament, as a result of which, naturally, the engineer Joseph Bazalgette was commissioned to construct a new system of brick tunnels to remove the offensive effluent a safe distance downstream. The first of these was opened in 1865 and the system completed ten years later. (If he hadn’t completed them on time, he would have been in the shit.) Much of the system he constructed is still in good lick today. It wasn’t until the beginning of the twentieth century that it was realised that discharging raw sewage into rivers and streams was a health hazard and the construction of treatment plants was begun. Although they had been around for years (the installation of one was supposed to have given Queen Elizabeth I great delight), Harry and Lily would have seen the gradual more general installation of the water closet, or flushable toilet. No doubt, down in Dorset, Lily would have been using an outside earth closet through most, if not all of her childhood. Lack of a piped water supply was the problem in many areas, but by the 1870s water closets were becoming common in middle class homes, and by the turn of the century the fully plumbed in bathroom was available for the well off.

Attacks on Victorian Christian Morality

Harry’s London was also the London of Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900), who was only one of many chipping away at the certainties of Victorian Christian morality. He was the Quentin Crisp of his day but probably even more outrageous considering the ethos of the time, and he would, I suspect, have been equally dismissive of the militant posturing of today’s lot. Oscar was a leading character in the Aesthetic movement, whose members placed art above everything, contending also that the sole purpose of art was to create beauty and it should have no moral purpose. And the artists and writers who were part of this movement deliberately set themselves up to dress and act in a manner apart from conventional society, thereby automatically raising the hackles of the conventional elite. For Oscar on top of all this, even though he was a brilliant playwright and author, to be openly homosexual was offending against the proprieties too much. He made known his passion for the young Lord Alfred Douglas thus stirring the enmity of Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, and from there it was all downhill. After two years in prison, with hard labour, for homosexuality, Oscar spent the last few years of his life in ill health and penury, living in France and Italy. But even at the end his wit did not desert him, when he wrote that he was “dying beyond my means”. I wonder what Harry’s thoughts were on all this?

Stirring the pot, aside from Oscar, were many others, from those producing theories which overturned the cosy world of evangelical religion, and those, like Oscar, who reacted against Victorian sexual morality, to those who agitated for reform of social inequalities. In 1859, while Harry was still bubbling quietly in his mothers womb, Charles Darwin had written his The Origin of the Species which blasted wide open the certainties of the generally accepted biblical teachings. The first edition of ‘Origins’ sold out in one day and caused instant controversy. If the Old Testament Bible was fiction, what happened to the Ten Commandments? No wonder much of the Victorian establishment looked upon ‘Origins’ as a subversive tract. (Unfortunately, to this day, not enough effort has been put into replacing the religious moral code with one based on a common sense assessment of the requirements for the survival of civilised society.) In the same year Samuel Smiles published his Self Help, which advocated individual industry, thrift, and self-improvement, together with minimum government, and which also was a best seller. Here was the Victorian Christian ethic of compassion struggling with the new world order of ‘the Devil take the hindmost’ espoused by Smiles and apparently now supported by Darwin’s theory that competition and selection were the natural order of things.

Marxists, Fabians, & Social Campaigners

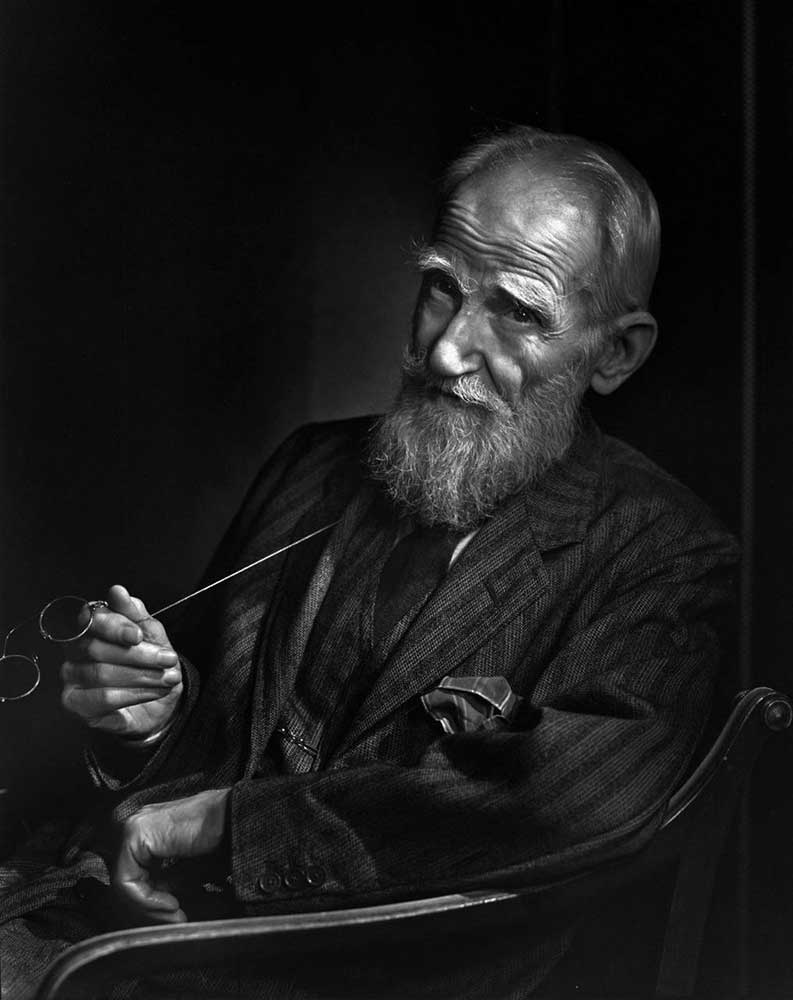

Unfortunately, this new world order was assigning an awful lot of people to the Devil and there were many trying to persuade the government and society to do something about it. Amongst those living in Harry’s London, working for change, and encouraging the proletariat to organise against their vile living and working conditions were Karl Marx (1818 – 1883), who wanted a revolution and who died in London, and George Bernard Shaw (1856 –1950), Sidney Webb (1859 – 1947), and Beatrice Potter (1858 – 1943) of the Fabian Society, who wanted change without revolution. Together with the trade unions and various socialist and Marxist organisations, the Fabians were instrumental in forming the Labour Representative Committee in 1900, the forerunner of the Labour Party.

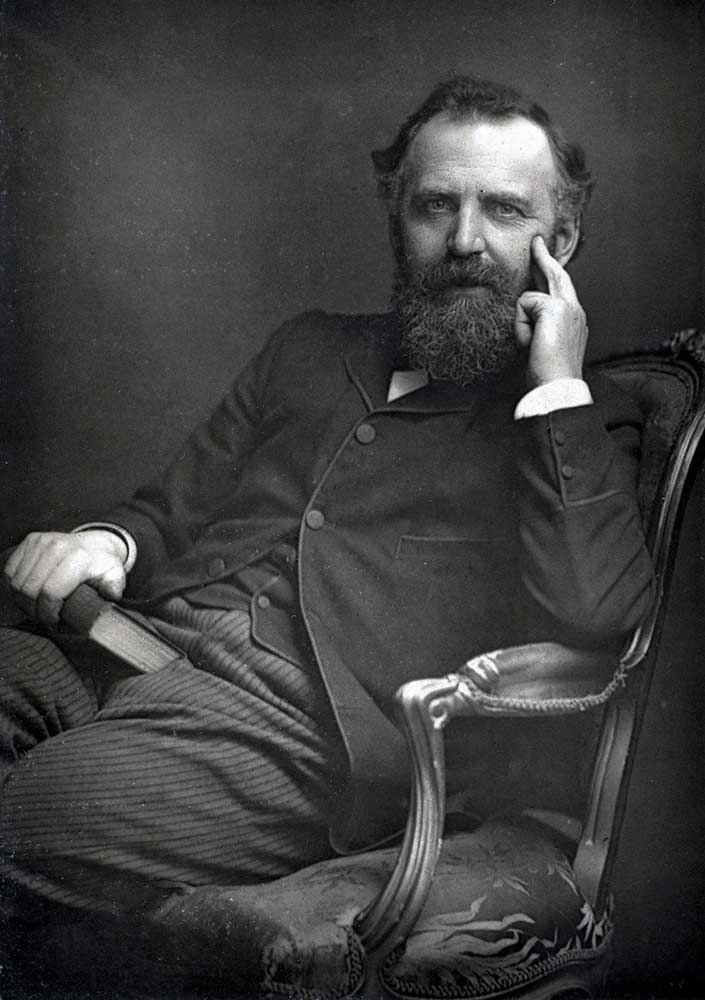

There were many other people actively voicing ideas diametrically opposed to those of the ruling classes, and among these were various writers stirring the Victorian conscience by describing the side of London they didn’t want to know about. Two of the most influential, and admittedly a bit before Harry’s time but still relevant even if things had improved somewhat, were Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870) and Henry Mayhew (1812 – 1887). Oliver Twist, probably Dickens’ most famous book, was published in 1838 and described a part of London called Jacob’s Island in the Borough of Southwark, which more affluent Londoners were mostly entirely ignorant of, and some of whom attempted to deny the very existence of. His description of the extreme degradation in which the inhabitants lived was in fact toned down in order not to offend the finer susceptibilities of his readers.

Both the Cholera outbreaks of 1832 and 1848 started in Jacob’s Island. A Cholera death is a vile one, victims suffering uncontrollable diarrhoea and dying in excruciating pain, their bodies still twitching hours after death. The epidemic of 1848 resulted in 14,000 such deaths. Cholera is spread by the victim’s waste contaminating the water supply, and was eventually stamped out in Europe and America by ensuring a properly treated fresh water supply. Henry Mayhew was a journalist who ventured, unusually, into Dickensian London and reported on it in great depth. His description of Jacob’s Island makes it quite clear why cholera flourished there – open drains leaving dark streaks down walls discharging sewage into the ditch, the abominable stench of the place, the disgusting greeny-black water choked with rotting animals, and people rotting in the ultimate stages of moral decline. His articles give vivid descriptions of East End inhabitants, ranging from the relatively upmarket costermongers, to the scavengers, known as ‘pure finders’, who eked out an existence by collecting the dog shit that was used in the tanning industry, or the ‘sewer hunters’ who risked their lives trawling through the sewer tunnels for any saleable items that had found their way into the system, and those lowest discards of society, the worn out or old prostitutes.

Prostitution and Drugs

I have recently finished reading Ben Elton’s High Society, a book which I can thoroughly recommend and, assuming that his depiction of the drug crime scene is close to real, leads me to conclude that we haven’t really advanced as much as most people think since the days of Dickens and Mayhew. The degradation in their day was one of poverty and social neglect, whereas the chaos of drugs, prostitution, and celebrity culture depicted by Elton in our own time is one of affluence, but with similar results. In Victorian times drugs were about although not on anything like the scale of today. It was cocaine for the rich and opium for everybody including the poor, and the degradation of the opium den and the gin palace matched the present drug ridden back streets and slave whorehouses depicted by Elton.

WT Stead, another Victorian campaigning journalist, although more in the tradition of today’s tabloid reporters, exposed the child prostitution going on at the time. He described in an article written in 1885, how a girl of thirteen was purchased from her parents for a sovereign (a one pound coin), taken to a brothel, and chloroformed before receiving her first customer. Elton describes how young homeless girls are taken off the streets, and kept under the influence of hard drugs in order to service brothel customers, in London, in the twenty-first century. (I am not sure whether Elton agrees with the solution of his main character, which is to legalise all drugs in order to take their supply out of the hands of the violent criminals who make millions from the current dreadful situation, but if so I don’t agree with him. I am afraid it fits in with the creeping paralysis engendered by modern liberalism, that has so neutered the effectiveness of society that it cannot deal with any major crime problem. There is already a huge problem with the legalised drugs – cigarettes and alcohol – so why add to it by legalising yet another mind bending substance which will only lengthen the queues at the psychiatrists door and add to prison overcrowding.)

Sexual Morality

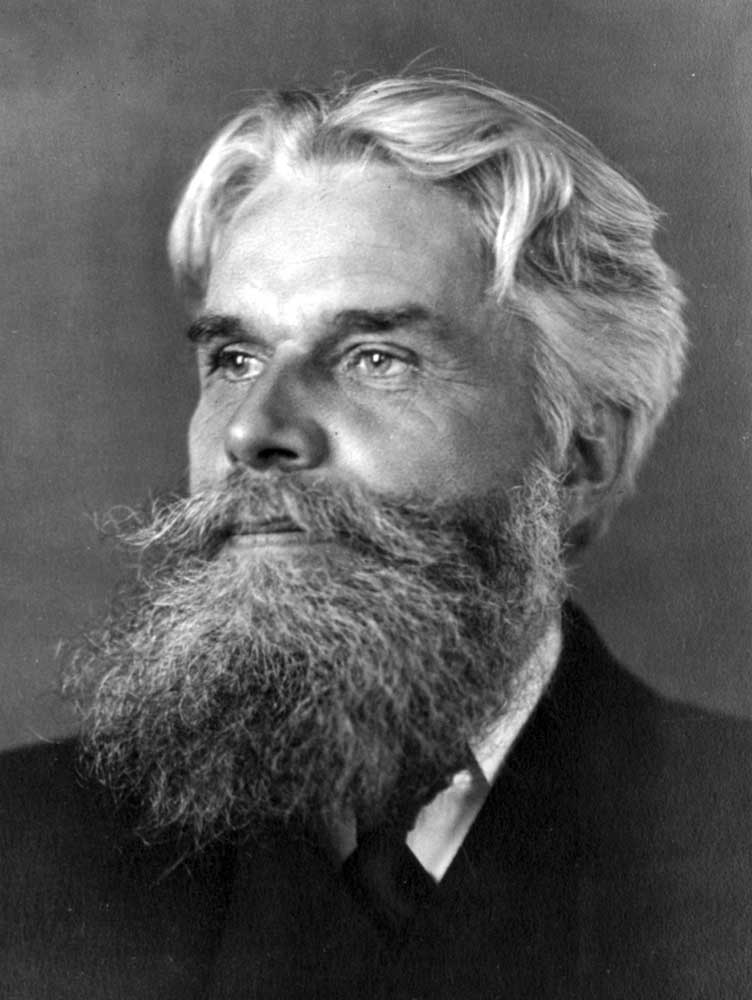

Battling against the current ethic of Christian sexual morality along with Oscar, was another contemporary of Harry; the psychologist, Havelock Ellis (1859 – 1939) His Studies in the Psychology of Sex, which acknowledged the importance of human sexuality, actually suggested that marriage was not necessary for sex to take place; something guaranteed to enrage as it challenged the bedrock of society at the turn of the century – the family. The seven volumes of this work, completed between 1897 and 1928, were only published in the USA and not in this country for many years, because the first attempt to publish met with legal action. He became better known to the general reader through his other books on sexual psychology such as Men and Women and The Erotic Rights of Women. Ellis courted disgust and censure amongst his contemporaries by, among other things, deriding the ideas that husbands should enjoy conjugal rights, that women should not enjoy sex, and that masturbation and homosexuality were unnatural. He even suggested that a prostitute selling herself to many men was no different to a wife selling herself to one man! Like many individuals strong on theory he screwed up big time in practice, marrying a woman with lesbian tendencies, having public affairs with prominent feminists, becoming impotent and getting his main sexual gratification from watching women urinate. Jolly sort of chap!

Harry, no doubt, in later life would not have overtly acknowledged or had much sympathy with people like Wilde, Ellis, the Fabians, and certainly not Karl Marx, or any of the other anti-establishment figures, because he was a man who provided a service to the establishment of the day and would have known where his bread was buttered. Certainly his writing, in as much as it departs from reporting on the social scene, reflects conventional Victorian conservative values and ventures little comment on any of the controversial issues of his day.

Part of a series: The World Of Harry Preston by Ron Woodlands

Ronald Philip Harry Woodlands (Ron) was the grandson of Harry Preston and his mistress

Ronald Philip Harry Woodlands (Ron) was the grandson of Harry Preston and his mistress