Harry’s move to Brighton and his entrepreneurial activities bring him into contact with the famous celebrities and early motorists and aviators of the day. He helps put Brighton back on the map and through his philanthropic work becomes friends with royalty…

This Page

Bournemouth to Brighton

The Panhard Motorcar & WG Grace

Exciting times for Entrepreneurs

Brighton Hotels and Celebrity Status

London by the Sea

The Raconteur, Impresario & Philanthropist

You’re the Tops, You’re Harry Preston

Harry’s Books

Harry & The Ripper?

A Passion for Bull-Terriers

A Changing World

Self-made Men

Harry’s War

Three cheers for Sergeant Preston!

Harry’s Strike

Harry’s Peace

Harry’s Sport

Madeira Drive Speed Trials & the Grand Brighton Aerial Race

First Flight... a Seaplane Adventure

My Lady Ada / Sussex Motor Yacht Club

Trouble at Sea

First Love

Royal Patrons

A Dear Friend Abdicates

End Game

A Recipe for Life

Funeral

Bournemouth to Brighton

In the early 1900s William Dore decided he wanted to form a company to run their hotels with himself and Harry as directors. Harry was having none of it, arguing that he wanted to be his own boss, not responsible to a board of directors and shareholders, but Dore was adamant and there was a clause in their partnership deed which allowed him to proceed with his ambition. They agreed to part, but amicably according to Harry who decided to move to Brighton. For a while he had a foot in both Bournemouth and Brighton, and as he wrote in Memories, “unable completely to leave the one and not ready by any means to burn my boats and devote entirely to the other”.

The Panhard Motorcar & WG Grace

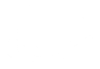

This latest endeavour would not have been possible without the arrival of the new four-cylinder car of which Harry had one of the first. Previous cars had either one huge cylinder or two smaller ones and were totally unreliable. He left his wife in control at Bournemouth, while he concentrated his attentions at Brighton, and shuttled frequently between the two in his gleaming new Panhard motorcar.

The law was having to catch up with technical innovation then as now. The Locomotives Act of 1865 had restricted speed to 14 mph but in 1903 the Motor Cars Act lifted this to 20 mph. It is doubtful if there were many speed cops policing the highways along the south coast at the time so it could be that Harry, returning from one or other of his hotels after a few tipples too many, might have thundered through the countryside at death defying speeds of up to perhaps twice this limit. He did the one hundred miles between the two locations in about four hours, which would certainly imply some speeds in excess of the limit, especially as there were three level crossings and the Southampton floating bridge to negotiate.

During this spell of early four-wheel transport the most famous cricketer of them all, WG Grace, who possessed that famous facial fungus, asked Harry for a lift to Hastings where he was playing. Harry agreed with the proviso that they needed to leave at lunchtime in order that no after-dark driving on acetylene lamps was involved. The great man got himself bowled out LBW in order to conform with Harry’s request.

Exciting times for Entrepreneurs

Harry recorded, with enthusiasm, that the world was entering a new pioneering phase during his latter days at Bournemouth and the early part of his career at Brighton:

There was a great surge, a movement of adventure and enterprise. Commerce was discovering new methods. New markets were opening up. New horizons were appearing. The gold discoveries in South Africa had brought new wealth to finance new projects whose potentialities seemed limitless. In science, trade, engineering, industry, in every field, young men with new ideas were breaking through crusted old traditions and making things hum. The age of advertising was opening.”

– Memories (1928)

He was right, of course. They were exciting times for thrusting young entrepreneurs like Harry and he meant to make the most of it. And who can blame him. But in Victorian and Edwardian Britain the winners were few and the losers many, with the losers often in desperate straits. Harry, no doubt like most of his ‘young men with new ideas’, would have lost little sleep over this on his climb to success, being too busy ensuring that he was a winner rather than a loser. But in later life he joined the philanthropic movement which from Victorian times represented the conscience of the English upper classes, the capitalist alternative to the welfare state, providing sustenance to the deserving needy.

In Memories, he goes on to relate numerous tales of the men he knew who had climbed to fame around the same time as himself. People like Lord Dewar, who made his fortune out of his brand of Scotch whiskey, Sir Thomas Lipton who made his out of tea, Guglielmo Marconi who stayed with Harry at the Grand Hotel and carried out his experiments with wireless telegraphy on Sandbanks at Poole Harbour, Jimmy White the ‘wizard of finance’, Sir Kingsley Wood the Conservative politician, and George Robey, known as the ‘prime minister of mirth’, who rose to fame as a music-hall comedian. Then there was Mr Bernhard Baron who built up the Carreras cigarette company in competition with such giants as Imperial Tobacco. He started as a non-English speaking Italian immigrant to America earning sixteen shillings a week in a tobacco company, and ended as a millionaire and philanthropist who gave much of his money away. Of course, that was in the days before cigarette manufacturers became lepers, and while smoking was thought to be a good thing, except for women.

Brighton Hotels and Celebrity Status

Around [1901] Harry purchased the Royal York Hotel at Brighton, which despite having once been the haunt of royalty was, when he purchased it, a ruin that had to be rebuilt from the bottom up, taking every penny he possessed. The result was an overdraft of £3,000, a tidy sum in those days and one which made his bank manager nervous, calling Harry in to account for himself, an event which Harry merely changed to his own advantage by changing bank managers. From this point on Harry built on his reputation with visits to his hotel by royalty and the political and entertainment elite. During this time he obviously cultivated useful contacts because in 1913 Sir John Blaker was influential in obtaining for Harry a knockdown price of £13,500 for the Royal Albion Hotel (asking price £30,000), and he also financed Harry for the first instalment with a cheque for £1,500. Blaker was an astute businessman who had achieved a fortune, mostly from property deals, and was at this time Chief Magistrate of Brighton. Harry says of him in ‘Memories’, “He was an Englishman to the backbone, and a staunch and living friend. There is no higher tribute I can pay than this.” The Albion had been closed down since 1900, and was in a very dilapidated state, but under Harry’s stewardship, the hotel became world famous, cultivating the rich and influential, and fully justifying Blaker’s faith in him.

‘London by the Sea’

He was largely responsible for returning Brighton to its previous status as a favoured seaside resort for the rich and famous. Royal patronage had earlier established Brighton as ‘London by the Sea’, almost the second capital, after Doctor Richard Russell of Brighton published his A Dissertation on the Use of Seawater in Diseases of the Glands in 1749. Russell’s insistence on the benefits of immersion in seawater gradually made Brighton fashionable, and by 1789 the Prince Regent, who was to be the future George IV, had moved there. The famed Brighton Pavilion was built for him by Nash to house his secret wife, a Catholic, Mrs FitzHerbert after he married her clandestinely in 1785 (the Act of Settlement of 1701 prohibited the succession of a Catholic to the throne). Brighton became the place for the aristocracy to be seen, which in turn, brought the artists and writers following in the wake of their patrons. However, the town suffered a decline in popularity when Queen Victoria deserted the Royal Pavilion after the death of Prince Albert in 1861 and retired to the seclusion of Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

Sir Harry’s Timeline

No time to read the full story?

Then scroll through the highlights of Sir Harry’s life in the Timeline…

This decline represented the challenge and the opportunity that Harry Preston’s entrepreneurial spirit required. He set to work with a will to turn his overdraft into a profit, his hotels from dereliction to opulence, and Brighton itself, from seediness to its former elegance. When the Daily Mail ran a derogatory article about Brighton, Harry went to remonstrate with the proprietor, Kennedy Jones, in person, and the interview was published on the front page. Of course, it wouldn’t be the same Brighton as in Regency times; the availability of travel by rail brought the ‘common herd’ to the seaside for day trips, but hotels such as the Royal Albion maintained that atmosphere of exclusivity attractive to those who could afford it. In 1931 Harry added the Mansion Hotel, also known as the Adelphi, to his hotel group in Brighton.

The Raconteur, Impresario & Philanthropist

Through his efforts to re-vitalise Brighton and his hotel ownership Harry became a celebrity and well-known local character, a raconteur and impresario. He became very active in various philanthropic activities, raising considerable amounts of money for charitable purposes. Always sporting a carnation, he was in the habit of smoking 12 Havana cigars a day and of drinking considerable quantities of vintage champagne and brandy.

He rubbed shoulders with many of the stage and film stars of his time: Sophie Tucker, Evelyn Laye, Jack Buchanan, George Robey, Nelson Keys, Wilkie Bard, Henry Irving, the American comedian Will Rogers, and numerous others, gave their services free to his Brighton charity concerts. He went on speed trials with Sir Malcolm Cambell (who broke the world speed record in 1927, doing 174 mph in his car ‘Bluebird’), flew with Sir Alan Cobham (who made the first round-the-world flight in 1926), and entertained or socialised with the famous. People like Noel Coward (playwright and actor who appeared in many films and wrote In Which We Serve and Brief Encounter), Gracie Fields (English singing star who became a national idol – ‘Our Gracie’), Herbert Wilcox (a famous film producer of the time), Ivor Novello (a famous composer, actor, and playwright), the Dolly Sisters (an early singing group), ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (who entertained London with his ‘Wild West’ show in Queen Victoria’s Jubilee year of 1887) and many others, knew Harry and stopped at his hotels or attended his charity events.

‘You’re the Tops, You’re Harry Preston’

The lyric of Cole Porter’s song You’re The Tops says: ‘You’re the tops, you’re Harry Preston.’ according to correspondence in the Daily Mail (have no date, but must have been during the 1980s because on the back of one of the cuttings is a reference to John Major) the Harry Preston in question is Sir Harry Preston of Brighton. Cole Porter (1893-1964) wrote the song in 1934, and according to a letter from a Betty Barron of the Sutton Coldfield Music Library, he did not include this line in his original lyrics, but the song lent itself to the addition of items by the recording artists. Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald, Ethel Murman, or Mel Torme could have added the line, among many others who recorded the song.

‘You’re The Top’, sung by the man himself Cole Porter (minus the ‘Harry Preston’ lyric)

Many of the literary figures of the day were acquainted with Harry. Arnold Bennett wrote his novel Clayhanger while staying at the Royal Albion. Harry went to various ‘gay’ parties (in the days when ‘gay’ meant having a jolly time and being serviced by the butler meant bringing the drinks round) at his and other hotels, and at various of the gentlemen’s clubs like Buck’s and Brook’s, with many literary types. People like Maurice Baring, the novelist, poet and playwright, the author Hilaire Belloc, GK Chesterton, author and journalist who wrote the ‘Father Brown’ stories featuring a priest who becomes detective, EV Lucas, a novelist and authority on Charles Lamb, Sir James Barrie who wrote The Admirable Chrichton and Peter Pan, and Arthur Machen the Welsh novelist and journalist. Jeffery Farnol, who wrote popular historical romances, was a great friend of his.

Harry’s Books

Perhaps under the influence of his literary friends, and towards the end of his life, Harry decided to have a go at writing. He wrote two books: Memories, published in 1928 and Leaves From My Unfinished Diary, published in 1936. He also wrote various articles on boxing and physical education. Much of the material in Leaves is covered again in Memories. One has to ask, what was the purpose? I wouldn’t have thought the books would have achieved a large circulation although as copies are still available, perhaps I am wrong, but it is unlikely he needed to go into print for the money. They are not autobiographical, but more a selection of anecdotes about his life and all the famous people he knew. They tell us practically nothing about his private life. So why did he write them? The need to be creative? Apparently, when he wrote his first book at the age of 69, he was still too busy to retire, so it wouldn’t have been for something to do. Possibly Harry, the great raconteur, was persuaded, after an evening on the Bollinger and while over the port and brandy, by some of his friends from the publishing world to set down on paper a selection of the stories he had been regaling the company with. This is how he explains it himself, in his foreword to Memories:

An hotel is a swing door through which the world walks – princes and peers, celebrities of Society, the turf, literature, art, sport, finance, the theatre, notorieties, and those men-and-women-in-the-street who, although their names are emblazoned on no roll of fame, are the backbone of the country, and full of interest to a student of character and of human life.

– Memories (1928)

The man who keeps this door sees from behind the scenes changes in fashions, manners, in life. He stands in the centre of a little world which reflects faithfully the great world outside, stirring, surging, changing, fighting, living. He sees, if he lives long enough, men before they rise, when they have risen; and sometimes he sees them – when they loose their grip – falling, and after they have fallen.

He sees, too, many novel aspects of people about whom the world has formed opinions often the reverse of accurate. Also, he is occasionally privileged to see a facet of character which a man, and especially a celebrated man, rarely, if ever, shows to the crowd.

The world has been walking through my swing door for half a century now, and this fact – added to my keen interest in all kinds of sport, and especially in boxing, which has brought me into contact with all sorts of distinguished people, celebrities and good fellows – must be my chief excuse for thinking that perhaps I can tell some stories which may possibly interest and amuse others besides my personal friends. In the last twenty years I have declined a good many offers from publishers who were optimistic enough to think that my recollections would interest people; and it was only in the spring of this year (1927) that I at last decided to succumb to an invitation. After all I have arrived at the age of sixty-nine. I add this, also, to the list of my excuses.”

Harry’s books give few clues about his attitude to any of the great social issues of the day, but perhaps the selection of writers he mentions, and more particularly those he leaves out, can give some idea of his thinking. All humanity ultimately divides into tribes, cliques, and clubs, by class, ethnicity, culture, gender, sexual orientation, politics, creed, ideology, or just the need to be different; and writers are no exception. Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953) and GK Chesterton (1874-1936), who were part of Harry’s circle, were bitterly opposed to the ideas of HG Wells and George Bernard Shaw, who were not. Wells (1866-1946), who wrote The War Of The Worlds amongst other well-known science fiction books, was a militant supporter of feminism, socialism, and evolutionism. Shaw (1856-1950) was a dramatist and critic, but also a well-known social reformer and member of the Fabian Society.

Also not mentioned as being within the circle of Harry’s literary acquaintances were people like DH Lawrence (1855-1930) who greatly offended conservative opinion with his Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) who similarly caused a stir, though not quite in such an extreme manner, with his Jude The Obscure. So, by association, Harry came down on the reactionary side of the fence, but the trouble with trying to analyse him from this is that he socialised as a career, and so met the writers that fitted in and mixed with the London and Brighton social set. It is probably unlikely that those writers that disagreed or diverted from the establishment’s idea of social normality would have engaged much in the club circuit that Harry describes. And, Arnold Bennett, who he knew and admired, was a friend of HG Wells and John Galsworthy, who satirised the British upper classes with his Forsyte Saga.

Harry & The Ripper?

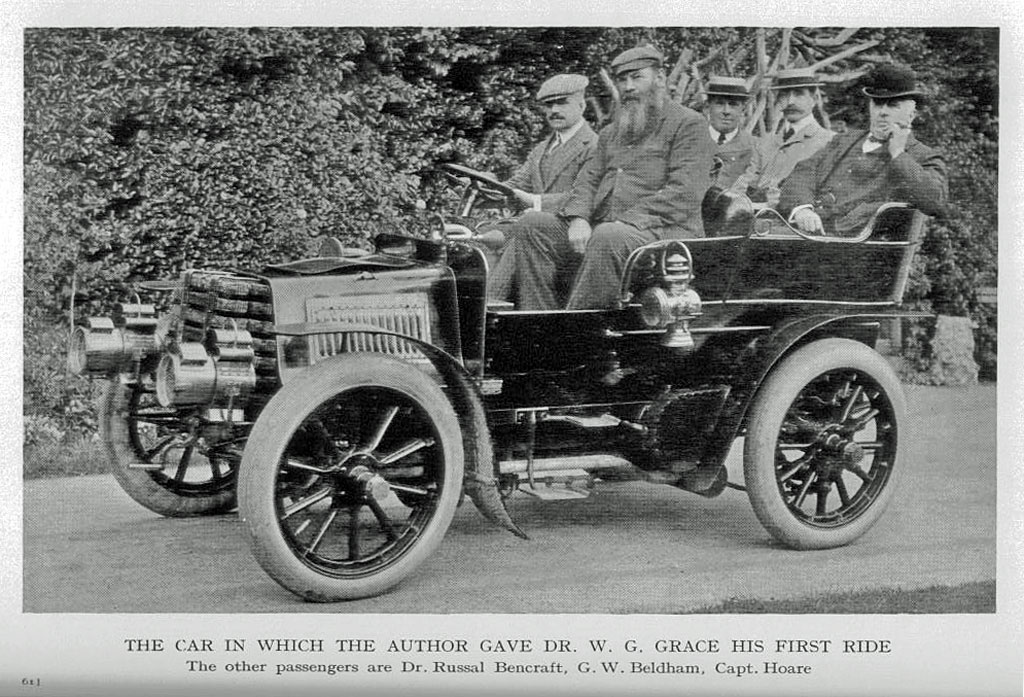

He also had some small contact with artistic circles. Well known cartoonists of the time, Tom Webster who worked for the Daily Mail, and Phil May, did numerous sketches for and of him. He was very friendly with Walter Sickert the painter, who did a portrait of Harry with his dog, Sambo.

Sickert was influenced by Whistler, who he was assistant to for a while, and Degas whom he met in Paris. Two of his paintings are exhibited at the Tate Gallery. After a spell abroad he went in for painting realistic scenes in and around the Camden Town area of London, and set up the Camden Town Group of artists in 1911. In the Group’s first show there were two paintings by Sickert entitled Camden Town Murder Series No.1 and No.2 which depicted nudes in drab boarding house rooms. In 1888 and 1889 the gruesome ‘Jack the Ripper’ murders had occurred in the Whitechapel area of London and Sickert was thought to have used the connection for publicity purposes.

There have been many candidates considered for the never discovered identity of the ‘Ripper’, but the American crime writer, Patricia Cornwell, has fingered our Walter. So Harry just might have been holding hands with a throat slitter and mutilator of London prostitutes!

A Passion for Bull-Terriers

Hygiene regulations not being what they are now he kept quite a large menagerie in his various hotels, including apes, jackdaws, and parrots. But he was passionate about bull-terriers which he bred and admired for their spirit – they could, of course, be relied upon to take large pieces out of anybody that tried it on with Harry, that is if he couldn’t manage it himself!

His greatest favourite was a bull-terrier called Sambo, a dog that was always to be found stationary in the front vestibule of either the Royal Albion or the Royal York, not moving in response to all the thousands of people who must have made a fuss of him over the years, but waiting steadfastly for his master to reappear. Sambo died in 1926 and warranted a long paragraph in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.

A Changing World

In ‘Leaves’ he contrasts the world in 1935 with his boyhood years, when ”Queen Victoria was on the throne and the world was very respectable”. He was firmly taken to church twice on Sundays, and points out that it was many years before he stopped feeling shocked (“and a little indignant”) by the growing practice of people to engage in card games and billiards matches on a Sunday. Surprisingly, there were apparently respectable people who lived together without being married. He mentions one such elderly couple who stayed regularly at his hotels, and who were so devoted to one another that when the man died, the woman seemed to will her own death within two days. However, it has to be said that these were reasonably affluent people or they would not have been able to stay frequently in hotels, and so could probably shrug off any censure. Poorer people were more likely to have the system stacked against them, because such a flouting of convention could lead to restrictions on social and job prospects. Nevertheless the rigid conventions of the time were starting to weaken even among the lower levels of society, possibly illustrated by the fact that women were starting to smoke although it has to be said, mostly only in private.

Self-Made Men

The story he tells of one Harry Lane undoubtedly illustrates the philosophy of his class of self-made Englishmen; the philosophy of individual industry, thrift, and self-improvement espoused by Samuel Smiles in his book Self Improvement published in 1859, which didn’t take any account of that essential ingredient, luck! The luck of being in the right place at the right time, of being born to the right parents, or simply of not hitting a run of bad luck. (Mind you, that is not to say that some of the current generation could not do with a dose of Samuel Smiles injected up the correct orifice.) Anyway, Harry Lane was an extremely successful gambler on the horses who won and lost fortunes, lived the high life, was known and respected by everybody, and finally went down in a big way, losing it all. Harry meets him later at Cruft’s Dog Show, on a stall selling tins of shoe polish which he demonstrated by cleaning people’s shoes. The tins contained Nugget Boot Polish, a new product taking over from the previously universally used shoe blacking. “And here was this middle-aged fellow who had lived like a prince, not softening up and asking people to do things for him, but tightening his jaw and getting down to real hard graft. For him to go down and black a man’s boots in order to push his wares was a big thing, a magnificent piece of courage.” (M) But Lane did have a few friends who got together and financed him with a hundred or two to set up his new polish business. He died worth a quarter of a million, and all the friends who had helped made a lot of money.

Harry’s War

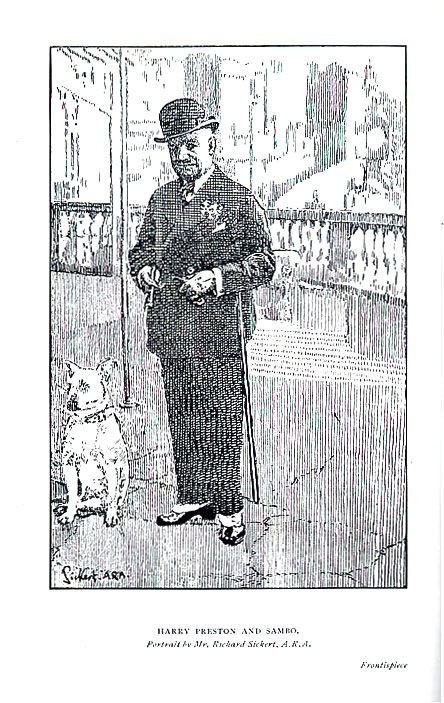

The Great War is mentioned once or twice in Memories. He offered the services of himself, aged 55, his brother Dick, aged 38 (the Richard shown aged 4 in the 1881 Census), and his sea going motor-yacht, My Lady Molly, to the Admiralty at the start of the war but after they explained they could not organise the war around his need to wander off at intervals to run his hotels he withdrew his personal offer of service. Dick accompanied the boat, modified with armour plate and Maxim gun, to the Suez Canal and Bitter Lakes for mine sweeping duties.

Because of the modifications his boat was only fit for the scrap yard after the war, so Harry at least made some financial contribution to the war effort.

While a guest of Commodore Reginald York Tyrwhitt aboard the Arethusa at Harwich he describes a Zeppelin raid:

We had a charming time, and were toasting the King . . . . when there was a boom, followed by a crash. It was a Zeppelin, the first to cross the strip of sea from the enemy land to raid our island. We were promptly bundled ashore, and the destroyer flotilla put to sea. But of course we couldn’t go to bed. We stayed on the cliff watching that wonderful little silvery cigar in the sky. The shrapnel from our guns burst underneath it, and far below, spattering the sky as it seemed aimlessly, like rockets sent up at a fête. I was immensely impressed by the helplessness of our defences against that little cigar shape that had brought its load of bombs and German airmen over the North Sea to strike a blow at our heart.

Or course our air defences improved enormously later on; but this spectacle made me realise that we weren’t bound to win the war simply because we were English. It brought home to me the hard fact that these fellows were formidable, and there were a good many things in England, on both the political and military sides, which needed improving if we were going to smash the enemy – and even keep him from getting his jack-boot heel on our throats. I could understand how it was – although it always enraged me – that some big financiers and famous business men and politicians now and then, when something went particularly wrong, and the outlook was very black, showed signs of wanting to make terms with the Germans.”

Interesting that! It suggests that there was a similar spell at the beginning of the First World War to that of the second, when Halifax and Chamberlain were advocating a deal with Hitler. Harry could ‘understand how it was’ because no doubt some of these financiers and businessmen were friends of his. He goes on to sing the praises of Mr Lloyd George who, he implies, took over and hardened the resolve of the British people in a similar manner to Churchill in the Second World War.

Three cheers for Sergeant Preston!

Harry’s brother Will (the William shown aged 18 in the 1881 Census), although only three years younger than Harry, was accepted for military service as a sergeant because of his previous experience in the Boer War. Serving in the front line at Ypres, Will received a large Billingsgate market box of kippers from Harry, and distributed them down the line to his troop, who had been through a cold November day without food because of some supply cock-up. Enjoying the meal, someone found out who the benefactor was and accordingly called for three cheers for Sergeant Preston. When the Germans heard a loud burst of cheering they thought it was the prelude for an attack and ordered an artillery bombardment!

During and after the war he helped members of the Eccentric Club to raise money for hostels for disabled servicemen. But other than these snippets, we learn very little about what Harry thought of it all, whether he knew anybody that was maimed or killed in the conflict or suffered any other personal tragedy. He wrote that he had a great deal of difficulty with the rationing regulations during the war, but nothing about how he managed or whether there was a shortage of either staff or visitors. Considering he brought the Royal Albion in 1913, only one year before the start of the war, one would have thought the four years of the war were critical. He does mention a young Guards officer ‘bearing a well-known name’ who dined with him at the York during a spot of leave, so perhaps he managed to keep going as a good port of call for the officer class on leave. But then, even more so than in the next war, many civilians did very well out of the conflict (a fact which was bitterly resented by the soldiers suffering the inhumanities at the front) so perhaps Harry’s hotels were full enough during this period for him to make a profit.

Harry’s Strike

He mentions his friend and mentor Sir John Blaker as being “the terror of conscientious objectors” during the war by serving as chairman of a military tribunal, and Blaker gets similar approval for the time during the General Strike of 1926 when, while presiding at the sessions, all the rioters and agitators brought up before him went to prison. As a result of both his service on the tribunal and at the sessions he received threatening letters and carried an automatic in his pocket, in case any of the anonymous senders tried to put their threats into action.

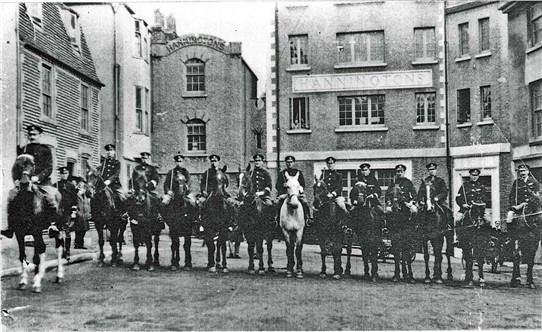

During the strike, Harry aged 68 served as a sergeant in the mounted specials where, provided with both a short and long baton, he also equipped himself with knuckle-dusters for protection if pulled from his horse. Both sides of the ‘class divide’ were fully prepared and willing to ‘mix it’ should the occasion demand. He makes the point that though he had thought for some fifteen years before the Great War that the conflict was not only possible but probable, he had never envisaged a general strike. The idea of the working classes organising on such a scale was getting too close to the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 in Russia; the possibility of anything similar happening in this country was not to be imagined and any inclinations that way firmly dealt with. Some of this thinking must have been passed on to his son, Jack Woodlands, because where Harry was representing the establishment on a horse, Jack was doing the same by driving a bus, risking violence by ‘strike breaking’.

After the General Strike my feelings for Labour leaders were none too sweet – although I must say that my relations with the Labour men in Brighton politics have been excellent and we have found a good deal to fight for in common. . . . . it was Mr JH Thomas who was the first man to heal – he did it quite unconsciously – the enmity that I felt towards Labour politicians whose action in May 1926 might easily have ruined millions – myself included (Harry’s hotels became mausoleums during the strike). Mr Thomas came and spent Easter at Brighton. We fraternised, reviving old memories over a glass of wine. There were three or four other men there, and he gave us the best laugh in weeks with his witty stories. He made politics and the affairs of state very human.”

– Memories (1928)

(Mr JH Thomas was general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers; MP for the Derby railway seat, and in 1929 was to become minister with special responsibilities for unemployment in the second Labour government. He was unsuccessful at preventing rising unemployment. There was never less than a million unemployed at the time of the General Strike – a figure which represented a far higher percentage of the population than it would do now, and left those unemployed in a far worse economic state than now – by 1933, when the unemployed of this country numbered some three million, it represented almost a quarter of the workforce without work, while some areas had levels of unemployment up to 90%.)

Later at “a joyous little dinner party” in a private room at the Garrick Club, Harry and assorted friends are bemoaning their lot. “Colonel Browning remarked that he didn’t know how men were going to pay their taxes in 1927. 1926 had been a calamity. No one had any money. And yet they were talking of increased taxation.” (Sad, really, they probably had to cut their dinner parties down to one a week and their ‘champers’ intake down to two bottles a day!)

Harry’s Peace

It is interesting to discover that writing in 1928, some ten years before the Second World War, Harry has begun to loose his enmity towards the Germans arising out of the First World War. He still had a policy of not accepting German wine in his cellars but his attitude was softened by a pleasant trip up the Rhine from Cologne to Berlin in the autumn of 1921. He relates how they met a Royal York Hotel ex-waiter who, being German, had been interned in Britain during the war, and who did Harry a good turn by acting as courier to his party. This man undoubtedly saved them money by negotiating the exchange rate on their behalf. Marks were then at 6,000 to the pound and “falling at the rate of about one extra nought a day”. Also interesting is his admiration for one Prince Piero Colona, Mussolini’s “chief of Italian Fascists in these islands”, for whom he helped find suitable accommodation in Britain. However, in hindsight many things become clear, and it is easy to criticise the people who without this benefit of hindsight acted as they did. In the twenties and thirties many of those who were not pacifists (probably one of the strongest influences then because of a reaction to the horror of the Great War) thought the main threat was from Communist Russia of which Hitler and Mussolini were natural enemies. And the political establishment of Britain and France were busy signing bits of paper supposedly guaranteeing peace.

In 1921 Hitler became president of the National Socialist Workers’ Party, mostly known as the Nazi Party. By the beginning of 1922 the German mark was plummeting out of control at over 30,000 marks to the pound and was to carry on downwards. This financial disaster was to be the catalyst for Hitler’s climb to power. In the October of that year Benito Mussolini’s Blackshirts seized Rome and he began to establish his Fascist dictatorship.

In 1925 the Treaty of Locarno was signed. This was a non-aggression pact between France, Germany, and Belgium, which was hailed as a landmark in human history, and as ushering in an era of eternal peace by Sir Austen Chamberlain of Britain and Aristide Briand of France. This was followed in 1928 by the Kellogg – Briand Pact, signed by fifteen nations and later ratified by many more, which renounced war and agreed to resolve all disagreements by ‘pacific means’. Then, as now, there was a perception that talking and signing bits of paper would keep the nasties at bay. In reality they do nothing of the sort, but many people at the time, like Harry, can be excused for failing to understand the looming menace of the Nazis in Germany and the Fascists in Italy. The majority view, until it was too late, was that major wars were outdated and that peace must be striven for at almost any cost, a very similar attitude to the ‘peaceniks’ at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and equally counter-productive. In a mere ten years the world was to erupt into major conflict once more, fighting the evil of a totalitarian takeover of Europe.

Harry’s Sport

In his second book, Leaves From My Unwritten Diary, written in 1935 when he was 76, a year before he died he explains that dates meant little to him, so that when he was asked to write his memoirs he did not have a diary to refer to. Referring to his life as an hotelier he says:

The truth is I have kept a swing door for more than half a century, and through it have passed all sorts and kinds of people. Between many of them and myself there has been struck the magic spark that kindles that best of all things – friendship. And if I number princes among my friends as well as politicians and pugilists, it is because one dash of sport makes the whole world kin.”

– Leaves From My Unwritten Diary (1936)

Undoubtedly, sport was Harry’s great enthusiasm and his success as a hotelier allowed him to combine business with pleasure, by entertaining both the great sportsmen of the day together with the notable sports enthusiasts. Using his early knowledge and experience as an amateur boxer in London he gradually worked towards becoming very active in the sponsorship of the sport and knew most of the major people in the fight game at the time. His books tell many a tale about the champions, including Jack Dempsey (the Manassa Mauler who became world heavyweight boxing champion in 1919), Gene Tunney (who took over the title from Dempsey in 1926), Max Baer, Joe Louis, Peterson, Corbett, and many others. His expertise on boxing both as promoter and participant was of a high level. He comments as follows:

The endurance of a modern boxer fighting twenty rounds is astonishing. Wonderful as they were, I doubt if the old-timers could have survived it. They did not know as much as we do about the science of hitting. A blow with a gloved hand, scientifically delivered, is harder than a blow from a naked fist, even when that fist has been carefully pickled. Heads, chins, cheekbones, shoulders, and ribs are very tough things to drive your naked fist against. Many an old-time bare-fist fighter had his knuckles driven in by contact with an opponent’s bone. Knuckles are relatively fragile things, and I dare say that if a physiologist went carefully into the whole technical question, he would find that the modern boxing glove is kinder to him who gives than to him who receives!” – – “This tenderness and fragility of the knuckle joints led to a man being careful about his blows. As he did not want to break his hands he seldom struck full force.”

– Leaves From My Unwritten Diary (1936)

In Memories he talks about the code that existed between ‘the boys’ and ‘well-known sports and famous gentlemen’ at the boxing matches arranged by The National Sporting Club. ‘The boys’ were the criminals and pick-pockets that worked the racecourses and other sporting venues, but who had such respect for ‘sports’ that a word in the right direction would obtain the return unharmed of valuable articles stolen at the ringside, knowing that the ‘sport’ would make no mention of the affair to the police.

Madeira Drive Speed Trials & the Grand Brighton Aerial Race

You name it, if it was sport Harry was interested in it and mostly at one time or another took part in it. Boxing, cycling, yachting, swimming, rowing, horse riding, flying, and motoring, were all sports that he actively enjoyed. If there was a club of any note catering to the needs of the sport he seemed to belong to it. And, of course, he knew all the top sporting personalities. In 1905 he organised, against local opposition, to have a section of the front at Brighton put down to tarmac in order to stage a motor race. In 1911, at Harry’s instigation, the first aeroplane to fly into Brighton landed on the beach, breaking its propeller in doing so and taking sixty-five minutes to fly the forty miles between the resort and Brooklands, from where it had taken off. The pilot had nearly landed at Worthing, but leaning out of his cockpit realised his mistake because there was only one pier and he knew Brighton had two. Shortly after that, with brother Dick, Harry arranged the first cross-country aeroplane flying competition in Britain, from Brooklands to Brighton, the planes flying round the pier and landing at Shoreham aerodrome. The winner, who claimed a gold cup, completed the forty or so miles in 57 minutes and 10 seconds. Naturally much of this activity was to publicise both Brighton as a resort and Harry’s hotel as the place to stop in while there.

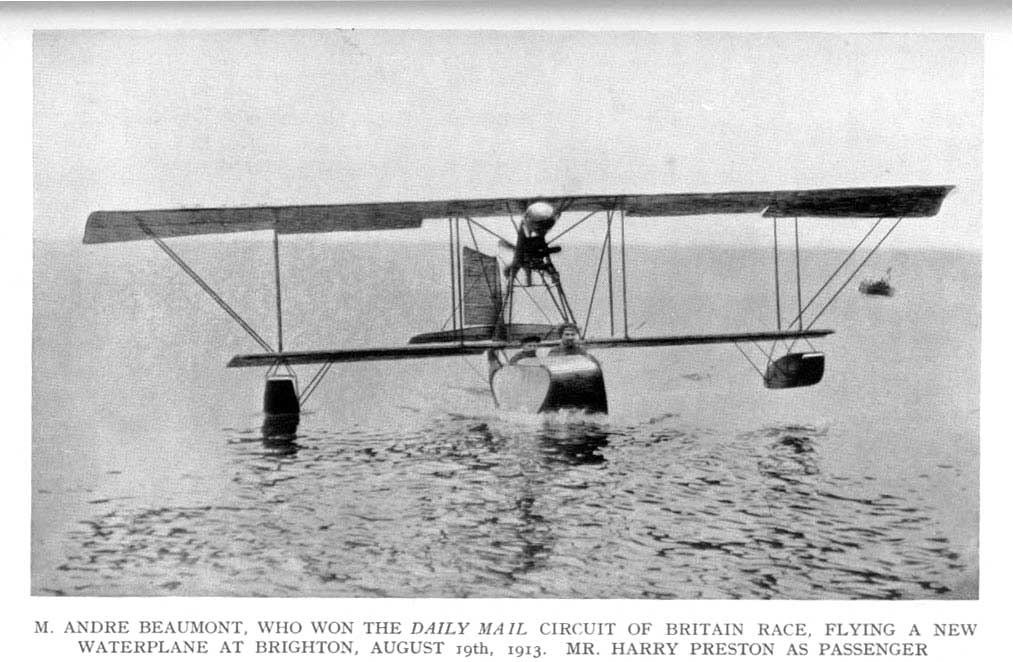

First Flight… a Seaplane Adventure

Nevertheless, publicity seeking or not, Harry was not afraid to take part himself in any of the activities he promoted. A gentleman called André Beaumont took him up for his first ever flight. Beaumont had brought the seaplane over in pieces from Dieppe and put it together on the beach at Brighton. “It looked as if he had knocked it up out of soap boxes and piano wire.” Once the engine started the whole contraption shook as though it was going to fall apart, and the take off across the water was accompanied by much rocking and shaking. After three-quarters of an hour they landed with a splash.

How did he know Beaumont? “They were great boys, those pioneers of the air. I knew them all. Their photos, mostly signed, adorn the smoking- room of the Albion.” Of course, Harry was an early member of the Royal Aero Club! Among the other clubs he held membership of, most of which existed for promoting and encouraging sport, were the National Sporting, International Sportsmen’s, Motor Yacht (Brighton), Eccentric, and Kennel clubs.

My Lady Ada / Sussex Motor Yacht Club

When he exchanged Bournemouth for Brighton, and thereby a more successful but pressurised life, he had to give up sailing. Wanting still to spend some of his reduced leisure time on the water, he invested in a craft more suitable for the up and coming entrepreneur, especially one whose enterprise was firmly based at a south coast resort. My Lady Ada was for quite a while the only motor-cruiser on the stretch of coast local to Brighton and gained Harry membership of the Sussex Motor Yacht Club, where he was elected Rear-Commodore, and given access to yet more of the wealthy elite. He also became acquainted with various senior officers in the Royal Navy, through My Lady Ada being used as an unofficial Brighton ‘flagship’ to ferry the mayor out to greet a visiting torpedo boat flotilla. “The Commander met us on board the flagship. Something passed between us as we gripped hands – the gleam, the spark of fellowship.” (Knowing the Navy as I do, the Commander was probably thinking, ‘This bloke looks good for a great run ashore – an introduction to some crumpet, nice grub and a good piss-up’.) Harry gave the Commander and companions breakfast before an official visit to the town hall. Johannesburg hock with the fish, Pommery with the kidney and bacon, and liqueurs with the toast and marmalade, before staggering off to meet the Mayor and various dignitaries. (So they missed out on the crumpet – but they had three more days, so I expect the missing ingredient was eventually supplied.)

Trouble at Sea

Before leaving, the Commander invited Harry to Portsmouth and he used the occasion to ask for a lift for himself and brother Dick to Ventnor on the Isle of Wight, to visit their sisters. “We scudded down the Channel in great style. How those lean black dogs o’ war raced through the water, belching smoke from their red-hot innards!” But, when the time came to leave Ventnor the weather had deteriorated and they climbed aboard the whaler with difficulty in a rising sea. As the whaler attempted to discharge its passengers back on to the destroyer that had brought them, a heavy sea rolled it over. The whaler was completely submerged leaving Harry, Dick, and the whaler’s crew scrambling for their lives up the lifelines, which fortunately had been lowered to assist boarding. The whaler was completely lost, but guess who presided at the official enquiry into the loss? None other than the Commander who had authorised the unofficial trip in the first place. There would have been a few free gins and privileges given out to get the right words entered in the report, no doubt.

This incident was not the last where Harry experienced near disaster at sea. During a London to Cowes race in 1911 his state of the art sixty-foot yacht, with seventy-five horsepower engine, was disabled in heavy seas off Newhaven after nightfall. An engine fire led to loss of power and then total engine failure. Drifting helplessly towards heavy breakers thundering on the shoreline, they sent up flares, with no response. He mentions with some disgust that the Liberal Government had cut down on the coastguard as an economy measure. They did not have enough life belts to go round so improvised with empty petrol cans, and when the boat grounded managed to struggle ashore through the breakers. The boat was salvaged and re- commissioned.

First Love

But in the end, all these other sporting activities were mere distractions from Harry’s first love – boxing. “Boxing helps to develop and bring out every one of those qualities that make a man a man. . . In the Boer War it was discovered that those soldiers that stood their ground best had been keen on boxing.” (Possibly Harry learned this incontrovertible fact from younger brother Will, who did service in the Boer war. William shown as 18 in the 1881 Census, would have been 36 by 1899 when the Boer War started.)

Afterwards the Army officially took up the once ‘disreputable’ sport. . . . Two or three years after the war the Germans had made boxing a compulsory part of their army training. The Germans had found out what boxing had done for the British character, and wanted to imitate England, the mother of boxing.”

(A lot of this now sounds bombastic nonsense but it was for a different age, when the reality of going out to fight for the ‘mother country’ was often a necessity. There was probably some truth in Harry’s assertion about boxing, in that it could give the experience necessary to achieve the physical and moral strength which, allied to the discipline of military training, could make the difference between victory or defeat on the battlefield. The current conviction that a general ‘love-in’ will occur and that such militaristic skills will never be required on a major scale again is almost certainly false.)

In my youth and early manhood boxing was a hole-in-the-corner business. It is only in recent years that it has risen to the status of a society function. Charlie Mitchell, who got six weeks for participating in a fight that my brother-in-law, Teddy Bayly, arranged, said the most pungent thing about this that I can recollect: ‘Nowadays they get paid three thousand quid for going into the ring for three minutes. In my day we stopped in the ring for three hours and got six months – if we were unlucky.’

– Memories (1928)

Many a time I have refereed boxing contests at the autumn manoeuvres in the old days, when the ring was pitched behind bushes in some remote spot. Boxing was barely countenanced. It was left to NCOs and sporting subalterns not troubled with a highly developed sense of good form. The Prince of Wales definitely ended all this nonsense by attending a boxing tournament in person. The Prince, an athlete himself, is an excellent judge of a fight.

Thirty or forty years ago people took it for granted that boxers were rough cards who would hit a man as soon as look at him. This, of course, was never true. But the stupid prejudices that surrounded boxing in the old days – and by the ‘old days’ I mean up to the World War – may seem incredible today (1928), yet they were very real yesterday. In the midst of the war Dick Burge and some others were told officially that they could not hold in the Albert Hall a boxing tournament in aid of the Hero Boxers’ Fund ‘because pugilism was not the sort of thing to be associated with a building erected to the memory of Prince Albert!’

Well, well! Time changes all things. His Royal Highness in 1921 greatly honoured me with his company at the Wilde-Herman fight in this same hall. The war had by then swept men’s minds clean of the last cobwebs of snobbery and humbug left over from the Victorian era. The insult to boxers as men, and to boxing as a manly and honourable sport, implied by that war-time refusal to stage a boxing match for charity in the Albert hall, was wiped out.”

Harry was obviously deeply attached to his favourite sport, but although there may have been some truth in his statement regarding boxing, the idea that the First World War had swept away snobbery and humbug would have been regarded as laughable by many of his compatriots. But I find it fascinating that boxing was considered such a reprehensible activity during Victorian times. In an age when personal violence was so much more likely than now and when the manly qualities of courage, discipline, and fortitude in adversity were still felt useful attributes and ones worthwhile learning, it surprises me that one of the activities that might be felt to teach these qualities would be frowned upon. But apparently it was a class thing – it was a favourite sport of the lower classes. Until 1892, when it was made legal, but still looked upon as disreputable by many, matches were held in out of the way locations, corruption was rife, and the rules were for bending, being indeterminate. After 1892 the Queensberry Rules were adopted and a higher class of patron began to attend boxing matches.

Harry relates how, in 1921, he was commissioned by his friend Lord Dalziel to report on the Carpentier-Dempsey fight in the United States for a fee of £250. His friend Jeffery Farnol was reporting the fight for the Daily Mail. On the night of the fight the ringside seats were crowded with British and American personalities, including Henry Ford and Douglas Fairbanks. The Frenchman Georges Carpentier displayed the ‘Verdun spirit’ when after giving his all in a spirited attack on the larger and heavier American ‘fighting machine’, and despite inflicting considerable damage, realised that Dempsey was not going to ‘go down’. With a thumb broken in two places and a sprained wrist he battled on through further punishment to final annihilation.

Royal Patrons

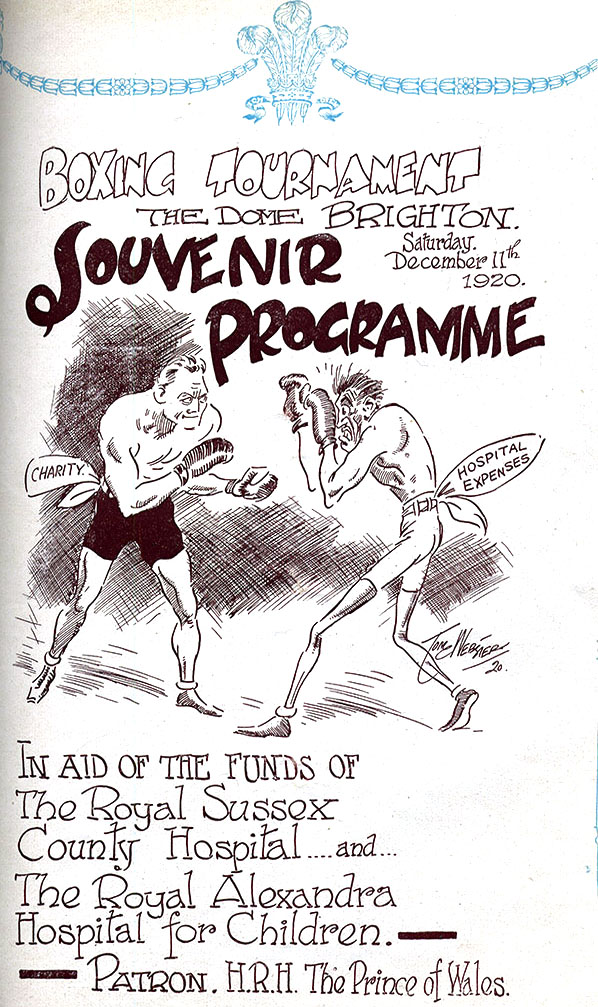

Harry’s increasing success with his Brighton hotel venture and his philanthropic activities eventually led him into the august company of Edward, Prince of Wales (later to become King Edward VIII), and his brothers George, Duke of York (later to become King George VI), and George, Duke of Kent. From 1920 he staged a boxing tournament yearly in the Brighton Dome in aid of the Royal Sussex County Hospital and the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children.

This event was a huge success, raising a great deal of money for these hospitals, because Harry managed to enlist the voluntary services of many top rank boxers and both the Prince of Wales and Duke of York as patrons. Harry gave exhibition bouts himself and the Prince would attend, stopping in the Royal Albion. And Harry had the honour of being invited to dine with the Prince at both Manor House Hove and St James Palace.

A Dear Friend Abdicates

Harry died in August 1936 after a lengthy illness so he may not have been in a position to worry much about the Abdication Crisis of that year. What would he have thought about it if he had lived a little longer? His friend the Prince of Wales became Edward VIII in January 1936 on the death of his father George V. Not long after he became involved with an American woman, Mrs Wallis Simpson, and in the summer of that year openly went on a cruise with her. Edward had always been a bit of a rebel, often flouting convention, which perhaps was why he sometimes joined Harry at still officially illegal boxing matches. He enraged the government under Baldwin by becoming political, speaking out about the plight of the unemployed in this country and admiring what Hitler was doing for the workless of Germany. Ribbentrop, who was then German Ambassador to Britain, was a friend of Wallis, so naturally this suave German became well acquainted with the King of England. Because Edward was privy to much information, including top-level cabinet discussions, he became a high security risk. In October Mrs Simpson obtained a divorce and Edward announced he wanted to marry her. At the top levels of the British establishment this was considered entirely undesirable – British kings did not marry divorcees, or Americans. He had to go. In December 1936 he abdicated – the only British monarch ever to have done so!

End Game

Harry did a lot of charitable work, raising money for local hospitals and boy’s clubs, running general sporting events and promoting boxing tournaments with famous participants for this purpose. He is remembered in Brighton to this day and there were a series of articles about his life in the Brighton and Hove Gazette and Herald as late as 1983. The Brighton and Hove website in 2004 has some of its pages devoted to him.

He became a Brighton town councillor in 1926, and retired from business in 1929, giving him six years or so in his cottage at Cuckfield in Sussex before he died. In Memories he wrote:

. . . like most men getting on in years, and very keenly aware that they have not too much time left in which to enjoy the sun and the wind, the wine and the good fellowship, of this bright earth, I have my dreams of leisure, hours when I plan what I will do with days that are now full – too full. . . . . I have a few acres, with rather a beautiful garden, and some bull-terriers and ponies and a horse, a fountain and a stream and some ducks, and an old-world cottage on which I and my wife have expended some care and thought, and to which I have gradually transferred sentimental treasures in the way of books and pictures and the nicknacks given to me by friends whom I love; and here, one of these days, if I continue to live, I shall retire to enjoy the leisure which I cannot find now.”

– Memories (1928)

This was written in 1927, when he was 69 and within two years he had retired. The King knighted him on July 12, 1933. He died aged 77 in August 1936, in his private suite at the Albion Hotel, of cancer, after many months of illness. His death was attended by tragedy for someone other than Harry and his family. Captain Ernest Chandler, only 45 years old, who was the secretary of Harry’s great friend the author Jeffrey Farnol, volunteered to give Harry blood for a transfusion, and as a consequence died a few days later of acute septicaemia. Chandler was similar in many ways to Harry, except being over six feet in height he towered over his friend, but enjoyed the same sporting enthusiasms, including having been a champion amateur boxer. He died not knowing that the transfusion had failed to save Harry, and Harry was never aware of the younger man’s ultimate sacrifice.

Unfortunately it seems that because of his illness Harry left his dreams of idyllic retirement a little too late to put into practice and fully enjoy. Puzzling, really, that such an apparently wealthy man should on the one hand dream of leisurely times at his long planned country retreat, and on the other, work until he nearly dropped. Apparently the cancer was diagnosed many years before. He relates in Memories how he was sent to a specialist for a medical check-up just before the war in 1914, when he was aged 55. Much later, in 1927, he was informed, by the doctor who had sent him for the check, that the specialist had diagnosed a malignant tumour and given Harry eight years to live at most. It had been considered best not to inform him. Harry, who was still very fit in 1927, and his doctor friend, perceived a certain dark humour in the fact that the specialist had died a few months before!

A Recipe for Life

I find, looking back from the present, where so much time and effort is spent on advising us how to survive for a few extra hours of dotage by not even thinking about doing anything dangerous, like breathing, that Harry’s attitude to the matter of healthy living is quite refreshing. He finds a friend of his dying. The doctors, having given up, allow him any reasonably vice such as the tablespoonful of inferior champagne administered by the nurse every quarter of an hour. Harry rattles off, returning shortly with a bottle of 1874 Pommery from his wine cellars, and manages to get a glassful of the vintage liquid down his dying friend’s throat. The friend recovered, living on for many years, and presented him with a beautifully engraved walking stick as a memento.

His enlightened attitude to food was perhaps surprising when you consider the massive over-eating which was engaged in as a matter of course by many of the rich in Georgian and Victorian times, and was still an indulgence of some of the upper classes in Harry’s later life, if not in quite such a profligate manner. And his ideas about living life fully and healthily are also worthy of note being based on common sense, rather than much of the claptrap we get today, full of extreme diets and advice to avoid most things that give life any pleasure. He comments in Memories:

I often see men in the late forties, fat, full-habited, stertorous men, John Bullish fellows, eating and drinking away, and I can see their end not so far ahead just as surely as if I knew they had a fatal slow disease. Only one thing can save them – physical work, exercise, a shake-up and a sweat-out of some sort, and that taken regularly.

– Memories (1928)

There was a well-known barrister who used to stay with me a lot. He was on the right side of fifty, big, robust. He ate enormous meals, and after his dinner would nod. He had an idea that he must eat hard to support his big frame, whereas what he ought to have done was to cut down some of the frame.

Although he appeared in perfect health I knew he was booked for the long trip very soon. And so convinced was I that he was eating himself to death, that if he were late for dinner or breakfast I used to send up to his room – I was afraid that the stroke that was hanging over him like the sword of Damocles had fallen. And a month or two later it did fall. He had a stroke in London and died.

Kennedy Jones (newspaper magnate of the time) is a typical example of the fine, virile man who will work and rush himself to death. He literally ran his engine at full throttle over the precipice. For years he had been in the vortex. He would not allow himself proper time for meals or rest. He ought to have knocked off at one and lunched quietly and returned at three. Instead, he would rush out, gobble a chop, swallow a drink, and hurry back to his desk. Or he would bolt a sandwich and a whisky-and-soda in the office. This man worth more than a million! This power in the land! That is real tragedy.

He had to have an operation, then another. He had simply ruined his stomach, his digestive apparatus, by ill-treating it over a number of years. I could tell of scores of similar cases.”

(Was Harry in the position of the man in a glass house heaving pebbles about? After all, he kept working until around the age of 70 although wealthy enough to stop, while still bemoaning his unfulfilled dream of rural retirement. ‘Ah would some power the gift to give us, to see ourselves as others see us’)

The chief function of my working life has been to welcome, cajole, calm, charm, make everyone feel at home, well-looked after and happy. But many a morning after a heavy night I have risen feeling like death. I have dreaded contact with life and people. I haven’t had a smile in me, let alone a laugh.

But I have struggled up; my man has pulled thick woollen vests and sweaters over me; my porters have brought my bicycle and almost lifted me on to it. A mile, and I have felt a little better. Then, off the bicycle, and a little walk and run, and, as the perspiration starts, the clouds roll away from soul and brain and the sun comes up. Life takes on a new aspect. Troubles diminish.

I attribute the comparative soundness of my own fleshy envelope less to a natural strong constitution than to unremitting care and attention, day after day and week after week, a day without food every now and then, and the best the rest of the time, plenty of exercise and a daily sweat. Exercise – of the intelligence as well as of the body: that word contains in a nutshell my recipe for keeping fit, happy and smiling.

Every man, of course, has to find what suits him best. But this is my recipe. My maxims are: Understand yourself. Manage and organise your life. Don’t let your body run to stomach, or your brain run to seed. Sweat once a day; it keeps you young and fresh. Snatch those half- hours of leisure which everyone has, and squeeze out of them the last moment of exercise, relaxation or rest. These, blended, compose the magic cocktail of happiness, healthiness, laughter and long life.”

Harry’s function as a leading hotelier through the early part of the twentieth century often involved the personal entertainment of his upper class clientele. Obviously, this would lead to almost unavoidable over-indulgence, for which he wisely compensated by living relatively frugally at other times, and having a rigorous exercise routine right through to the last years of his life. It has to be pointed out that he had certain advantages: a personal valet for one, and his porters to ‘lift him on to his bicycle’. Nevertheless, his philosophy in the face of what could easily have degenerated into a gluttonous, intemperate lifestyle has to be admired, and saw him through to his 77th year, which for the 1930s was a very reasonable age to achieve.

Funeral

Harry’s funeral service was held at the Brighton Parish Church followed by the interment at Cuckfield. Hundreds of wreaths and bunches of flowers filled motor coaches and cars, coming from Buckingham Palace, St James Palace, his various clubs, the local hospitals, various Brighton sporting organisations and clubs, and all the hotels and traders. A permanent memorial was set up in the form of a new wing at the Royal Sussex County Hospital.

Part of a series: The World Of Harry Preston by Ron Woodlands

Read more

Ronald Philip Harry Woodlands (Ron) was the grandson of Harry Preston and his mistress

Ronald Philip Harry Woodlands (Ron) was the grandson of Harry Preston and his mistress