From a middle-class upbringing, to teacher in Lewisham, shipping clerk in the City and London publican. The young sportsman develops his boxing skills, stages illegal boxing bouts at his London alehouses, meets his first wife, and heads to Bournemouth to begin a career in the hotel trade…

A Victorian Family

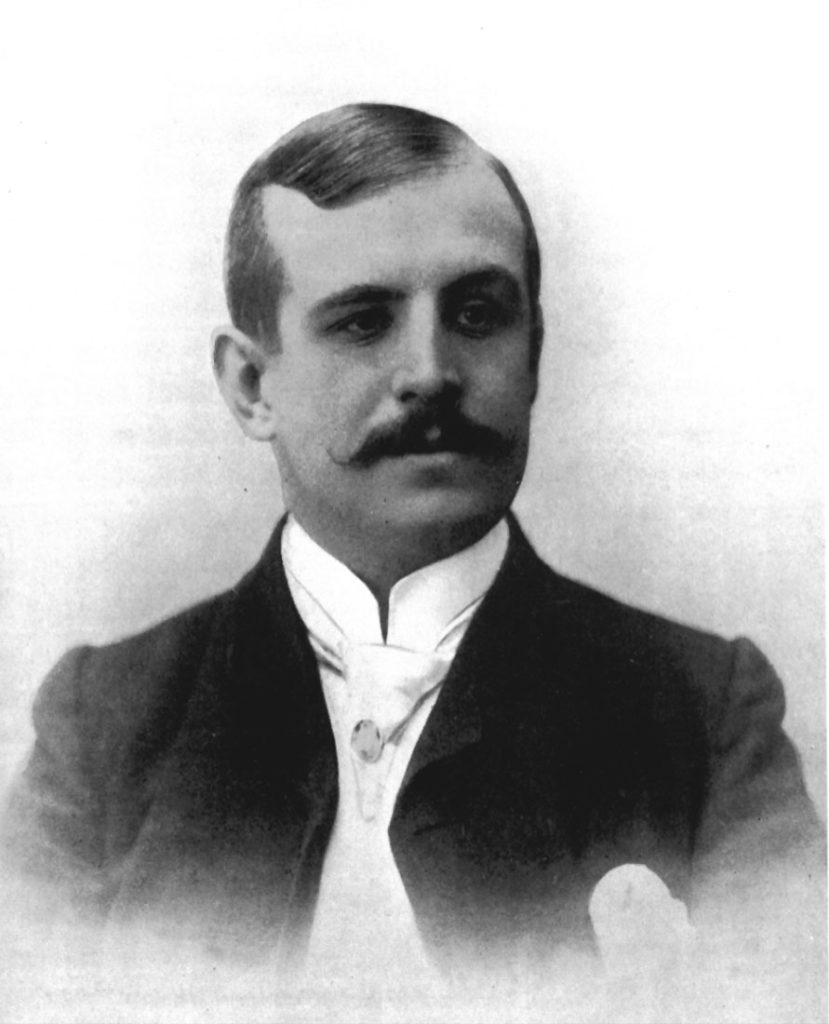

Henry John (Harry) Preston was born in the year 1860 into a middle-class family in Queen Street, Cheltenham. Whereas the middle-classes now comprise some three-quarters of the population, the proportion lucky enough to fit into that affluent designation in Victorian England was tiny by comparison. Possibly when Harry was born the family was not terribly affluent, in fact probably not even middle class, but certainly would have been by the 1881 Census when he is shown as aged 21 and his father, John aged 44 and then earning his living as a solicitors managing clerk. 21 years before John senior would have been at the start of his career, a much more lowly clerk, but nevertheless an occupation requiring a level of education denied to many at the time, especially as he came from quite lowly stock. When he married Helen Eliza Lovesey in October 1857 in Cheltenham Gloucester, the marriage certificate gives the profession of his father, also John, as a plasterer, so perhaps it is surprising that Harry’s father managed to get himself educated to the standard required for clerking.

Schooling was hit and miss then, being mostly provided by charity or church schools, and even after the act of 1870 that required children under ten to receive fulltime schooling, many children were still in work, some even from the tender age of five. Much depended on the financial needs of the family they came from. If desperately poor, the pressure for parents to urge their children into paid employment was tremendous. Of course education, of various degrees of suitability, was always available for those who could afford it, but it seems doubtful that a plasterer at that time would have possessed the wherewithal to pay even basic fees. John senior would have been going to school sometime between the years 1841, when he was 5, to 1851, when he was 15. The marriage certificate of 1857 only notes ‘full’, under the age column for both John and Helen, which was quite common at the time and denotes ‘of full age’ which could often be taken as the age of consent; in some areas being even younger than sixteen. However, assuming the ages given on the 1881 Census are correct, John would have been 21, and Ellen 22 in 1857. Surprisingly, he is described as a widower, so he was presumably married before.

Siblings

By the time of the 1881 Census, however, [Harry’s father] was affluent enough for the family to have a 15-year-old servant, Ada Pridmore, which considering the size of the family – John aged 44, wife Ellen aged 45, 4 daughters, 5 sons, one niece (Louisa Lovesey), and a lodger – must have been hard work for her, and required a large house and sizeable income. The location was certainly in an affluent area: Tadema Road, close to the river in Chelsea.

Whether Harry had any older siblings who had left home by the time of this census is not known, but living with him at Tadema Road was one elder sister, Mary aged 22, and seven younger siblings: George aged 19, William 18, Nellie 13, Frank 12, Winnefred 11, Beatrice 9, and Richard 4.

Early Career

When Harry was born the family lived in Cheltenham, Gloucester, which was even then a relatively well-to-do part of the country. Christened Henry John, but apparently always known as Harry, he was educated privately and initially obeyed his father’s desire that he follow a scholastic career by becoming a pupil teacher in Lewisham, Kent, for three years. But he was not happy as a trainee teacher and later described the episode as the longest years of his life.

He escaped to London, “the hub of the world” as he describes it, for a job in a city office. As a clerk working for various shipbrokers, he met life in the raw by talking to the sailors and skippers who had sailed and traded around the world.

The Young Sportsman

Outside of his job he put his abundant energies into various sporting activities, including sculling, swimming, and boxing. His main enthusiasm was boxing; but at only five foot one inch in height and weighing just eight stone he was extremely handicapped because at the time there were only three fighting classes, light, middle, and heavy. Now he would be classified as a bantamweight, but at the time Harry completely ignored such considerations and battered many a taller and heavier opponent into submission.

Boxing Club

Boxing was a sport considered unsuitable for people in genteel occupations and Harry kept his membership of a boxing club quiet at the shipping office. A black eye had to be disguised with a patch and story about it weeping because of a chill. The boss, a remote upper-class gentleman, could in that day and age fire people for the smallest indiscretion, so Harry was dismayed to find him a spectator at one of his fights and even more alarmed when summoned to his office the following day. Much to his surprise, however, Harry was congratulated rather than fired from which experience he drew the lesson “that the touch of sportsmanship levels all ranks and classes and callings, and strikes a common chord always among men who are men”(M).

Sir Harry’s Timeline

No time to read the full story?

Then scroll through the highlights of Sir Harry’s life in the Timeline…

Naturally, fighting at such a disadvantage he took considerable punishment from time to time. Receiving a massive blow to the ear in one boxing match, he continued to fight on in further bouts during the finals of the amateur boxing championships until, much to his disgust, the referee stopped him from continuing on the advice of the attendant doctor. The ear was extremely painful and hugely swollen. Harry’s doctor told him it would have to be removed, but Harry went to a specialist who fixed it without such a drastic option, but before doing so took a plaster cast of the bloated acoustic receiver. Years later Harry met the same specialist who was using the plaster cast as both a memento of a successful treatment and as a paperweight!

Penny-Farthing Bike Rides

Amongst all the other of Harry’s sporting endeavours he found time to fit in cycling. He and companions enjoyed travelling to Brighton and back on their penny-farthing cycles, leaving early in the morning and getting back at seven or eight at night. One of his companions was the chap who held the record – a mile in three minutes, which is 20 miles per hour. Some going on one of those things. Assuming they could manage to average 15 miles per hour, the 60 miles to Brighton would have taken 4 hours without stops! Must have been a very tough day, perched on a tiny saddle above the huge spoked wheel, some 5 ft in diameter, with its solid rubber tyre. The name penny-farthing came by comparison of the size of the front and rear wheels to that of the coins of the day – the large penny and the diminutive farthing – and the machine was also known as the Ordinary.

A Penny Farthing Race from 1928

The modern style bicycle with a chain to compensate for the loss of gearing gained by the larger wheel of the Ordinary came along in the 1890s, and was initially looked on with scorn by enthusiasts of the penny-farthing. But this innovation ushered in the age of mass-production, leading on to improved road surfaces and the motorcar. It also produced social changes which shook Victorian society to the roots. It made the ordinary person mobile, able to make friends and form relationships well away from their home village or town. And women, who could never ride a penny-farthing in skirts, were now able to take to the saddle of the new machines. Some were even – shock, horror – to be found cycling un- chaperoned and in trousers!

A ‘Charity’ Performance

Illustrating Harry’s confidence and outgoing personality is the story, in his book Memories, of forming an amateur nigger minstrel troupe during his time working in the offices of an East India merchant. Nigger minstrels were an extremely popular entertainment of the time. After numerous successful performances for charity in various town halls, Harry and his troupe decided a bit of charity their own way would not go amiss. Aiming high they booked a plush hall in the West End of London, managed to engage support artists, and sold more than twice the number of tickets than there were seats in the hall. Despite the irate protests of the many disappointed customers, Harry and his friends divided several hundred pounds between them.

A Change Of Career

Rubbing up against the more exotic worlds of sailors and sportsmen suddenly made Harry’s world of clerking look lifeless and dull by comparison. He conceived the youthful ambition to escape from the humdrum and compete with other men on equal terms as a man of substance, a man who was his own boss; to which end he resolved to enter the commercial hospitality industry. Interestingly, his parent’s marriage certificate of 1857 records that Helen, his mother, had an inn-keeper father, so perhaps Harry had a role model in his maternal grandfather. No doubt he did not recognise it at the time, but Harry possessed in abundance the necessary qualities to become a successful entrepreneur in the hotel trade. A hard driving and where necessary ruthless ability coupled with the essential courage to take risks, was mitigated by a charming and extrovert personality which made it easy for him to cultivate friends and acquaintances. Sounds like the recipe for a con artist, but Harry genuinely liked people and his success was to be achieved by hard work and enterprise.

The Publican

Astutely recognising his need to learn his chosen trade from the bottom up he started by running several hostelries of low repute in London. The first of these, in The Borough at the south end of London Bridge, had a large room used as a gymnasium in which Harry sometimes arranged boxing matches, which was then apparently still a crime under an Act passed three centuries previously. He narrowly avoided trouble when the law called the day following a fight and found discarded boxing gloves and sawdust. Although not charged, because of lack of conclusive evidence, he found his next application for a licence to run a pub in Hackney foundering because of opposition from the police officer who had visited his Borough establishment. Harry was not a ‘fit’ person because of the suspicion that he was involved in illegal boxing bouts. Out came the Harry charm, which mixed with an obvious middle-class background, was enough to convince the two or three ‘sports’ amongst the magistrates of his side of the case, and he got his licence subject to an undertaking not to stage fights on the premises. There was no room for boxing in this establishment anyway, but in his next pub in Holborn Harry carried on breaking the law occasionally with fights in the large room next to the bar. On the opposite side of the street was the ‘Thieves’ Kitchen’, run by an Irish lady of some repute called Mrs McCarthy and frequented by the Victorian London criminal fraternity, so Harry would have had little trouble in recruiting either fighters or spectators.

Moving on once more to another pub in a rough area on the riverside at Lambeth, he talks about an incident during his time there:

One evening three tough customers came in and caused trouble – They looked at me, and saw that I was a little fellow. They set about me. I was fit and lively then. I quickly dropped the first fellow with a bang on the jaw and fell on him. The other two piled on top of me. I seized the man under me by the ears and banged his head on the floor. I kicked out and got from under, The other two were lumbering fellows who new nothing about real fighting. In a few minutes one decided that he had had enough, and went out by the door. The third man, finding himself alone, followed him.”

– Leaves From My Unwritten Diary (1936)

I might perhaps have written this off as romantic exaggeration, selective memory, or just plain bullshit, except that when I was serving my time as a young apprentice in the Navy there was a lad in the same entry as myself who was of similar size and weight as Harry and equally as lethal. He, like Harry, took on people much taller and heavier and battered them to a pulp in our periodic boxing championships, and I witnessed him annihilate three toughs at the Glasgow Locarno dance hall, a place where you were frisked for knives before entry. Size is not always a requirement for hard-men and there is no doubt that Harry was a tough cookie in his youth and early manhood. It was an age which was inclined to produce Harry’s “men who are men” in greater numbers than today, because as he wrote:

People were much readier to fight in those days than they are now. When I look back I seem to see a world where rows over women, card games, or just arising out of sheer high spirits, were so frequent that there were insults every week, blows once a fortnight, and duels once a month. London clubmen occasionally popped over to the French beach to exchange shots.”

– Leaves From My Unwritten Diary (1936)

First Wife

In December 1885 Harry married his first wife, Ellen Boor. The address given for Harry is Southampton Street, Camberwell, and for Ellen, Queen Street, Brompton, so Harry had moved out of the East End, south of the river, and his bride had been living in an altogether more salubrious location to the west.

Ellen, the daughter of Joseph Lovelace, had been married at least once before. Her first husband was John Charles Edward Griessen, who she married in London, during December 1872. The marriage certificate gives her age as 21, which places her birth in 1851/2. In 1876, a child was born to the couple, but as so often in those days, tragically taken away shortly after by death. The couple moved to Germany sometime later, and a daughter named Lilian Dora was born there in 1878.

Ellen next appears in the 1881 Census, aged 30 (which agrees with being 21 in 1872), her status shown as married with the name of Duessen (almost certainly a misspelling of Griessen), and now living in Islington with her parents and daughter (aged 3), but apparently minus any husband. When she married Harry, who was then aged 25, in December 1885, she is entered on the marriage certificate as a widow, aged 27, by the name of Boor. But if the previous recorded ages of Ellen are correct, she was in fact then aged 34, some seven or eight years senior to Harry. Later, on the 1891 Census her age is given as 34, while on the 1901 Census it becomes 45! And finally, on her death certificate in July 1913, her age is given as 62, which again places her birth in 1851.

It appears Ellen was a lady who had great difficulty remembering her birth date! Did she deliberately deceive Harry about her age when she married him? It seems highly likely, because she knew her age only four years previously when it was correctly entered on the 1881 census return, although we could give her the benefit of the doubt by surmising she was an unorganised lady, who had lost all her previous records and had a poor memory for dates.

Daughter Ethel

But something other than the distortion of her age (which after all was looked upon as a natural thing which females at that time often did without much reproach) seems wrong about Ellen. On the 23rd of April, 1885, around eight months before she married Harry, she gave birth to another girl child named Ethel Maud Georgina Chitty, father George Chitty Boor, mother Ellen Boor formerly Lovelace, all according to the birth certificate. The birth was not registered until the 27th June, 1885 by Ellen, whose address was given as 32 Chesilton Road, Fulham. But George Chitty Boor, aged 54, had been busy dying of various ghastly complaints only ten days previously, on the 17th, far away in Wimborne Dorset, the informant being somebody apparently unrelated. No marriage between George Boor and Ellen has so far been discovered, and George, at the age of 50, is recorded as having married Georgina Can, aged 26, in 1881. After her marriage to Harry, Ellen’s child Ethel Maud was henceforth known as Ethel Maud Preston.

All of this presents us with various obvious questions:

Why did Ellen wait over two months, until after the death of Ethel’s father, to record the birth of her daughter?

Where was Georgina during this time and when George died?

Was Ethel really George Boor’s child, or was he used as a convenient way to give the child apparent legitimacy? The name on the birth certificate – Ethel Maud Georgina Chitty – suggests both George and Georgina connived in any deception, if there was one. But perhaps the young Georgina died shortly after George married her and Ellen happened along to comfort him in his loss? If so perhaps Ethel really was George Boor’s daughter.

Was Ethel fathered by Harry Preston as suggested by her surname change after he married Ellen? If so, why did Ellen and Harry not marry before Ellen’s birth, both being apparently unmarried?

These and other puzzles surrounding Harry and Ethel’s relationship may never be resolved, but if any of Harry’s descendants find the energy to dig, who knows?

Bournemouth and the Hotel Trade

After serving around five years apprenticeship in the hospitality industry, running pubs in the East End of London, Harry must have felt his experience was enough to head for better things. Accordingly, probably around 1887/8 when still in his twenties, Harry left London to establish himself in Bournemouth, and started the career in the hotel trade which was to lead to his establishment as a man of substance. Whether he went there entirely as a free agent, hoping for the best, or whether he knew of a job there, either through contacts, or through the press, is not known.

Part of a series: The World Of Harry Preston by Ron Woodlands

Ronald Philip Harry Woodlands (Ron) was the grandson of Harry Preston and his mistress

Ronald Philip Harry Woodlands (Ron) was the grandson of Harry Preston and his mistress